Political Movie Where a Movie Director Is Hired to Help With a Campaign

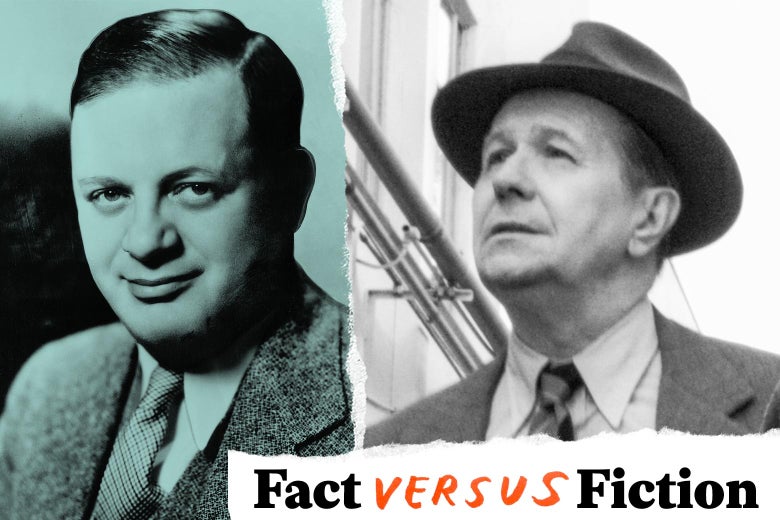

What's Fact and What's Fiction in Mank

Did Orson Welles cheat Citizen Kane's screenwriter out of credit? Did MGM film fake news to defeat Upton Sinclair's campaign for governor? We break it all down.

Mank, the new movie from director David Fincher about Citizen Kane's co-screenwriter Herman J. Mankiewicz, wades waist-deep into two contentious moments in American history and starts throwing punches. First and foremost, it's a movie about the writing of Citizen Kane, which spanned a couple of months in the spring and summer of 1940 and was briefly ground zero for the never-ending battle over auteurism. It's also, rather unexpectedly, a movie about the 1934 California gubernatorial campaign of Upton Sinclair, which was briefly ground zero for the never-ending battle between labor and capital. Much of what's on screen in both periods is more or less factual, but the screenplay, by Fincher's late father, Jack Fincher, draws a connection between those two battles that required a few adjustments to the historical record. Here's what's true, what's half-true, and what's entirely invented.

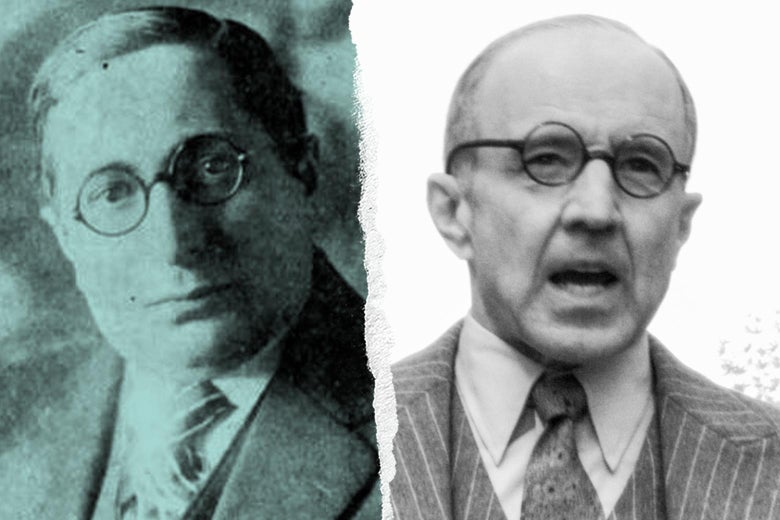

Herman J. Mankiewicz in Hollywood

Herman J. Mankiewicz (Gary Oldman) began his literary career as a journalist and sometime playwright, a member of the Algonquin Round Table who served as the original theater critic for the New Yorker. He came West in 1926 to write for the movies and never really left, although he also never really came to terms with being a screenwriter. His ties to the New York literary scene were valuable during the transition to sound: Studios wanted playwrights who had experience writing dialogue, so Mankiewicz helped recruit East Coast journalists as part of what he called "the Herman J. Mankiewicz Fresh Air Fund for Writers." According to Ben Hecht's 1954 memoir, A Child of the Century, Mankiewicz sent him a telegram reading:

Will you accept three hundred dollars to work for Paramount Pictures. All expenses paid. The three hundred is peanuts. Millions are to be grabbed out here and your only competition is idiots. Don't let this get around.

In Mank, a version of the telegram is sent to Charles Lederer (Joseph Cross) in 1930 and another character remarks that Herman has been sending them to "anyone who can rub three words together," but I couldn't find any evidence this happened in real life. Whatever his telegrams said, Herman helped assemble a murderer's row of East Coast talent at Paramount, including his younger brother Joseph L. Mankiewicz (Tom Pelphrey), whose career eclipsed Herman's own over the course of the 1930s. The most outrageous incident in this section of Mank, a scene in which Louis B. Mayer (Arliss Howard) tearfully asks his employees to take a temporary 50 percent pay cut during FDR's bank holiday, really happened, and Mayer really did promise to make his workers whole when the banks reopened, but never bothered to follow through.

In Hollywood, Mankiewicz quickly became legendary for his scathing wit and self-destructive behavior. He was an alcoholic and a compulsive gambler—Mank shows him betting Eddie Cantor (Derek Petropolis) $1,000 on a coin toss—and his addictions came with the usual problems in tow. Over the course of the 1930s, he drank, gambled, and insulted himself out of friendships and jobs, leaving his long-suffering wife, Sara (Tuppence Middleton), to pick up the pieces. Mank only has a couple of flashbacks that show Herman Mankiewicz at the studios, which means there's a lot of time compression at play—he didn't coin all of his wittiest retorts on a single day at Paramount in 1930—but although you could argue with some of the film's characterizations of studio executives as uniformly dimwitted (and Slate already has), the people and places in these scenes of the movie are more or less the right people in the right places.

Upton Sinclair's Campaign for Governor

Mank takes its cues from Citizen Kane wherever it can, so naturally it has a Rosebud-style mystery at its center: Why did Herman J. Mankiewicz write a script containing cruel caricatures of William Randolph Hearst and Marion Davies, both of whom he had known socially? It's not necessarily a great question to hang a movie on—Herman J. Mankiewicz's life was defined by hostility laundered through wit—but Mank finds an answer in the 1934 California gubernatorial race, and it's here that the film's relationship with history becomes more dubious (and more interesting).

Upton Sinclair had become a household name in 1906 for writing The Jungle, a novel about the meatpacking industry that helped spark health and safety reforms, and by the time by the time he moved to California in the 1920s, he was the country's most prominent socialist. In 1933 a Santa Monica businessman convinced him to run for the governorship as a Democrat. Sinclair, who was not in the habit of thinking small, laid out his plans for the state in a short book, modestly titled I, Governor of California, and How I Ended Poverty: A True Story of the Future .

Sign up for the Slate Culture newsletter

The best of movies, TV, books, music, and more, delivered to your inbox three times a week.

Sinclair's plan was enough to terrify the state's business leaders when he won the Democratic primary, and they mobilized to crush him. In the general election, Republican incumbent Frank Merriam defeated Sinclair 49 percent to 38 percent, with Progressive candidate Raymond L. Haight, who ran as a centrist, sucking up another 13 percent and possibly spoiling Sinclair.

Those events are the political backdrop Mank is playing with, and they're all true, but Herman J. Mankiewicz's relationship to those events seems to be Jack Fincher's invention. Mankiewicz's politics were complicated but mostly skewed conservative; Mank shows a little of this but downplays how public it was. There's a scene, for instance, showing Herman refusing to join the Screen Writers Guild in a private conversation with Joseph, but much of the dialogue actually comes from a full-page ad Herman took out in Variety taunting the would-be unionists, "You have nothing to lose but your brains." But if Mankiewicz was no unionist, he wasn't a fascist, either. Late in the film, a character reveals that Mankiewicz spent the 1930s helping refugees from fascism. This is true, although he didn't save an entire village, as Mank suggests. According to Sydney Ladensohn Stern's biography The Brothers Mankiewicz, he quietly sponsored refugees, helped them find work, and gave generously to relief organizations throughout the 1930s. And in 1933, Mankiewicz wrote and attempted to make The Mad Dog of Europe, an anti-Nazi film whose targets were so thinly veiled that the villain was named "Adolf Mitler." On the other hand, he was an isolationist who thought the United States stood no chance against the German war machine, going so far as to declare himself "an ultra-Lindbergh."

I couldn't find any evidence Mankiewicz supported Sinclair, much less that he carried a grudge for years over the campaign, and it seems likely he would have opposed him on the basis of prose style alone. Still, you can't pattern a movie after Citizen Kane unless your protagonist has an unhealable wound, so Mank seems to have made this one up.

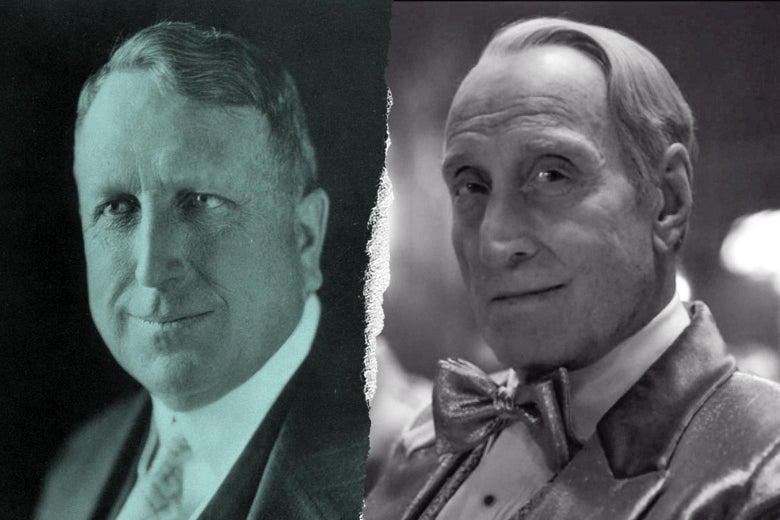

MGM's Fake Newsreels

California's right wing staged an all-hands-on-deck effort to stop Upton Sinclair from becoming governor, and that included newspapermen and studio heads. Hearst and Harry Chandler railed against Sinclair in their papers and Joseph Schenck, president of Twentieth Century Pictures, announced that he'd move his business to Florida if Sinclair were elected. Louis B. Mayer, state chairman of the Republican Party at the time, followed Schenck's lead, hinting he'd move MGM to Florida, and did all he could to convince his employees their jobs were on the line. Mayer came up with the idea of fundraising from his workers, asking every employee to donate a day's salary to Frank Merriam's campaign. ("Asking" is not really accurate: Rank-and-file employees simply had their "donations" deducted from their paychecks.)

All of that is shown in Mank in one way or another, but the Finchers steal a little valor to put Herman Mankiewicz in the middle of the fight. In The Campaign of the Century: Upton Sinclair's Race for Governor of California and the Birth of Media Politics, author Greg Mitchell identifies several writers who refused to donate to Merriam: Sam Marx, Frances Goodrich, and Albert Hackett at MGM as well as John Wexley and John Howard Lawson at Columbia, but not Herman Mankiewicz. (The scene in Mank in which Irving Thalberg attempts to talk Mankiewicz into a token donation seems to be modeled after Wexley's argument with Harry Cohn.)

Hollywood didn't just support Merriam financially. It also staged a sophisticated disinformation campaign, and it's here that Mank strays the furthest from the historical record. In the movie, Mankiewicz makes an offhand comment to Irving Thalberg that inspires Thalberg to produce a series of phony newsreels to help crush Sinclair. A friend of Mankiewicz's, test shot director Shelly Metcalf (Jamie McShane), leaps at the chance to step up to real directing and shoots a series of staged "man-in-the-street" interviews in which well-dressed white people explain why they are voting for Merriam, while foreigners, workmen, and Tom Joad types explain that they're voting for Sinclair.

After Sinclair loses the election, Metcalf has an attack of conscience—he's also despondent over a Parkinson's diagnosis—and kills himself on election night, despite Mankiewicz's attempt to intervene. Later, Mankiewicz, already beating himself up for inspiring Thalberg, discovers that Hearst helped fund the newsreels. It's straightforward, thematically apt, and gives the protagonist exactly the motivation the screenplay's structure requires. It's also a load of hooey. Not the newsreels: Thalberg really produced them, and they really ran in theaters all over the state, where they were presented to audiences as actual interviews. Here's the first film in what became a series of three.

Shelly Metcalf, however, is an invention. Thalberg's fake newsreels were directed by Felix Feist Jr., who, like Metcalf, was a test shot director looking to move up at MGM. In real life, however, his conscience seems to have been untroubled and his ploy worked: He directed short films throughout the 1930s before stepping up to features in the 1940s, moving on to television in the 1950s. He died of natural causes in 1965. Louis B. Mayer really did throw an election night party at the Trocadero, as seen in the movie, but if Herman Mankiewicz attended, it doesn't seem to have been documented. And although Mankiewicz would bet on anything, none of his biographers mention a bet with Mayer or Thalberg over the election results. (One thing they do mention is that Joseph L. Mankiewicz wrote a series of anti–Upton Sinclair propaganda for the radio, so if Herman felt strongly about the disinformation campaign, he had targets closer to home than Hearst.) Essentially, Mank paints an accurate picture of the forces that crushed Upton Sinclair's gubernatorial campaign, then rearranges things so that the election results break Herman J. Mankiewicz's heart.

William Randolph Hearst's Parties

The Mankiewicz family got to know newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst (Charles Dance) and his mistress, actress Marion Davies (Amanda Seyfried), through Davies' nephew Charles Lederer, and one of the film's highlights is its lavish recreation of Hearst holding court at his ludicrous castle in San Simeon. The Mankiewiczes really were there as guests several times, and Hearst really did value Mankiewicz for his dazzling conversation. The details of life at Hearst Castle are also correct and so are the broad outlines of Mankieicz's time there: His drinking slowly made him persona non grata until he was no longer welcome. Mank also gets Mankiewicz's friendship with Marion Davies more or less right: They bonded over their shared alcoholism, although according to Sara Mankiewicz, Herman mostly felt sorry for her. His final scene at Hearst castle, in which he pitches a Citizen Kane prototype that combines Hearst's actions in the 1934 election with Don Quixote, almost certainly never happened, because there's no evidence Herman cared about the Sinclair campaign. Finally, Mankiewicz did once say, after being violently ill, "Don't worry … the white wine came up with the fish," but he wasn't at Hearst Castle. He was at a dinner party thrown by producer Arthur Hornblow Jr., who was a notorious stickler for etiquette.

Marion Davies

Outside of San Simeon, Mank gives us enough glimpses of Marion Davies' career as an actress to make it clear that she was much more talented than Susan Alexander in Citizen Kane. She became Hearst's mistress around 1916, and in 1918 Hearst formed a production company, Cosmopolitan Pictures, to produce her films. Cosmopolitan didn't just have Marion Davies—it also had Hearst's publicity apparatus at its disposal, plus first dibs on any story material Hearst published, and the company easily secured distribution deals with studios. Although Davies' gifts were in light comedy, Hearst preferred her in period dramas, and, as seen in Mank, wanted Irving Thalberg to let her star in Marie Antoinette. When she didn't get the part, Hearst moved Cosmopolitan, and Marion Davies, and Marion Davies' 11-room bungalow on the studio lot, from MGM to Warner Bros.

This is all shown in Mank, but Fincher fudges the chronology a little to force an Upton Sinclair connection. In the film, Mankiewicz interrupts Davies' exit from MGM in a last-ditch effort to stop Thalberg's phony newsreels from being released. In reality, the first newsreel hit theaters on Oct. 19, 1934, Davies signed her contract with Warner Bros. on Oct. 31, Sinclair lost the election on Nov. 6, and Davies didn't actually leave MGM until Jan. 1, 1935. As for Davies making a trip to Victorville to try to convince Herman Mankiewicz to shelve Citizen Kane, it's vanishingly unlikely. Although the script seems to have made its way to Hearst and his lawyers through Davies' nephew Charles Lederer, in her memoir, The Times We Had: Life With William Randolph Hearst, she claims she never even watched the finished film.

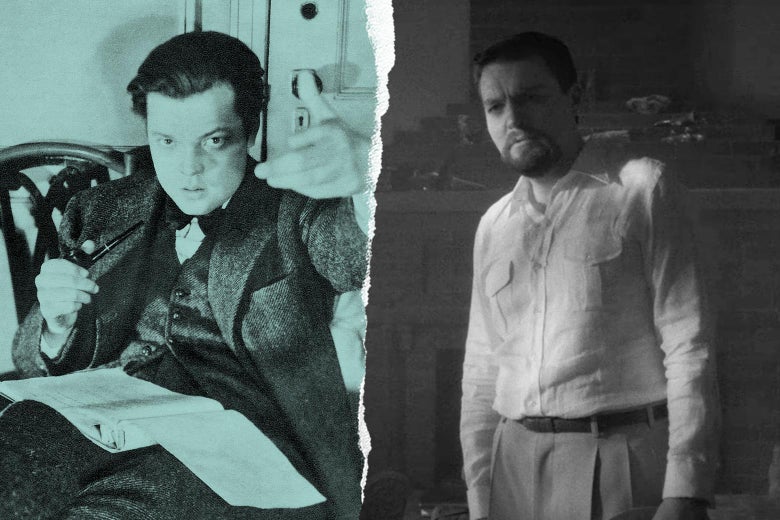

The Authorship of Citizen Kane

The heart of Mank is set during the months Mankiewicz spent at a ranch in Victorville, California, working on a draft of Citizen Kane while recovering from injuries sustained in a car crash. The authorship of Citizen Kane has been a subject of dispute since before a single frame was shot, and given the film's reputation, a bunch of people claim paternity.

There are countless different versions of the story of its creation, but they all agree on the basic setup. In September of 1939, Mankiewicz tried to catch a ride to New York with screenwriter Tommy Phipps, who, distracted, ran the car off the road, breaking Mankiewicz's leg in three places. During Mankiewicz's long and painful convalescence, Orson Welles hired him to write a few scripts for the Mercury Theatre radio show, and the two men began a fruitful collaboration. By December the two men settled on the idea of writing something about the life of a newspaper baron based on Hearst. Story conferences continued through January, and in the late winter, Mankiewicz decamped for the ranch in Victorville to write a rough draft. He was accompanied by Welles' one-time Mercury Theater compatriot John Houseman, a secretary named Rita Alexander, and a German nurse to care for his leg. The ranch was dry, but Mankiewicz's bottles of scotch laced with Seconal were probably invented. (According to Pauline Kael, Houseman brought some sort of drug intended to combat Mankiewicz's alcoholism, but it didn't work. Houseman recounts taking Mankiewicz to a local bar for a single scotch each night, which was quite a production on crutches.) Since writing a screenplay isn't the most cinematic activity, Fincher changes Alexander's husband—in real life, a recently arrived European refugee, according to Houseman—into an RAF pilot, which gives Mankiewicz a chance to put his foot in his mouth espousing isolationist views, but the basic conditions under which Mankeiwicz wrote his draft of Citizen Kane are pretty much correct.

When it comes to the actual writing, though, the different accounts of what happened become as prismatic as the life of Charles Foster Kane. There's no question that Mankiewicz signed a contract giving up any claim to credit. There's no question he later decided he wanted to be credited, argued with Welles about it, and eventually got his screen credit. But who actually wrote the movie? It depends who you ask.

If you asked Herman J. Mankiewicz, he'd tell you he was the sole author. Although neither he nor Welles attended the Academy Award ceremony where they shared the Oscar for Best Screenplay—the only award Kane got—he later said that his acceptance speech would have been, "I am very happy to accept this award in Mr. Welles' absence, because the script was written in Mr. Welles' absence." That's the position Pauline Kael argued in her 1971 New Yorker essay "Raising Kane," for which she interviewed John Houseman and Rita Alexander but not Orson Welles or any of his assistants. Alexander told her Welles "didn't write (or dictate) one line of the shooting script of Citizen Kane." Then there's the version Orson Welles told in 1972, for Peter Bogdanovich's Esquire article "The Kane Mutiny." Written in response to "Raising Kane" with input from Welles, it spends nearly as much time demolishing Kael's journalism as it does on the creation of Citizen Kane. In that telling, there were two first drafts, as Welles explained:

We'd started to waste too much time haggling. So, after mutual agreements on the story line and character, Mank went off with Houseman and did his version, while I stayed in Hollywood and wrote mine. At the end, naturally, I was the one who was making the picture, after all—who had to make the decisions. I used what I wanted of Mank's and, rightly or wrongly, kept what I liked of my own.

And then there's the account John Houseman gives in his 1972 memoir, Run-Through. Houseman was there to serve as an editor, as someone to bounce ideas off, and above all to keep Herman sober and working, but his version attempts to carve out his own contributions primarily through the use of the first-person plural:

We started with the image of a man—a giant, a tycoon, a glamour figure, a controller of public opinion, a legend in his own lifetime … As we talked we asked each other how this man had got to be the way he was, made the choices he did. In the process we discovered what persons were associated with him, we learned what brought them together and what he did with them and to them over the years. In deciding who was qualified, personally and historically, to tell his story and reflect his image, in selecting the "prisms" which would most clearly reveal the parts from which we must finally create a whole, we found the dramatic structure of the film gradually asserting itself.

Finally, there are the extant drafts of the screenplay, which Robert L. Carringer analyzed in a celebrated 1978 article, "The Scripts of Citizen Kane." Carringer's conclusion was that Mankiewicz was the primary author of the Victorville drafts, which stuck much more closely to the facts of Hearst's life than the final film, but also that Welles' revisions and contributions were "not only substantial but definitive." He also dug up a telegram Houseman sent Mankiewicz in June 1940 that makes it quite obvious that Welles was heavily involved in the development of the shooting script (and, furthermore, that Houseman was writing material as well, though it's anybody's guess if it was used).

The general critical consensus these days is that although there's no evidence to substantiate Welles' claim of having written his own first draft independently, his contributions transformed Mankiewicz's script "from a solid basis for a story into an authentic plan for a masterpiece," as Carringer put it. That is not how it happens in Mank, which essentially follows Pauline Kael's version of events. In some ways the Finchers go even further than Kael—and David Fincher has said in interviews that his father's original script was even more of an anti-Welles broadside.

In Fincher's film, all sorts of facts are shuffled to diminish other peoples' contributions to Citizen Kane. We never see any of the time Welles and Mankiewicz spent discussing Citizen Kane before Victorville, and there's no sign of the 300 pages of notes those meetings produced. Instead, Fincher gives us a gradually growing stack of notebooks next to Mankiewicz's bed as he creates the script out of thin air. In real life, John Houseman shared a two-bedroom suite at the ranch with Mankiewicz, the better to discuss the script, but Fincher ships him off, not just to a different room, but to a different hotel, to keep him out of the way during the writing. In "Raising Kane," Kael reprinted a rumor she'd heard from filmmaker Nunnally Johnson that Welles had offered Mankiewicz $10,000 to take his name off the film, which Welles has always denied. Fincher not only stages that incident; he has Welles get so angry about Mankiewicz's request for credit that he throws some furniture around, which inspires Mankiewicz to write the scene in Citizen Kane where Kane trashes Susan Alexander's room. That scene was inspired by one of Welles' tantrums, according to Houseman—Welles hurled lit Sterno cans at him—but this was months before any arguments about screen credit. In short, wherever Fincher could choose between different accounts, he chose the one that gave the most credit to Mankiewicz and the least credit to Welles.

Political Movie Where a Movie Director Is Hired to Help With a Campaign

Source: https://slate.com/culture/2020/11/mank-movie-accuracy-david-fincher-upton-sinclair-netflix.html

0 Response to "Political Movie Where a Movie Director Is Hired to Help With a Campaign"

Post a Comment